Appendiceal Neoplasms – 32 Interesting Facts

- Appendiceal neoplasms are benign and malignant neoplasms that arise from epithelial or neuroendocrine cells within the appendix

- Appendiceal neoplasms are broadly divided into epithelial neoplasms and NENs

- Epithelial neoplasms consist of invasive neoplasms (eg, appendiceal adenocarcinoma, goblet cell adenocarcinoma) and noninvasive neoplasms (eg, LAMN, HAMN)

- NENs can range from well-differentiated NETs to poorly differentiated NECs

- PMP is a clinical finding that describes the diffuse spread of mucin throughout the peritoneum

- PMP most often occurs from a ruptured LAMN, resulting in peritoneal spread of acellular mucin

- Less commonly, PMP may occur with spread of cellular mucin; cellular PMP can be classified according to the presence of low-grade histologic features, high-grade histologic features, or signet ring cells

- Appendiceal neoplasms are rare; the incidence is approximately 0.97 per 100,000 people34

- Appendiceal neoplasms are most often diagnosed incidentally in the surgical specimen after an appendectomy

- Preoperative suspicion for appendiceal neoplasms most often occurs after cross-sectional imaging performed when evaluating patients for suspected appendicitis

- A thorough history and physical examination are key in the evaluation of patients with suspected (or confirmed) appendiceal neoplasm

- Patients may present with concomitant appendicitis, because appendiceal neoplasms may cause secondary appendicitis

- Cross-sectional imaging, most commonly a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis, is often performed for the workup of appendicitis

- CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis can often suggest an appendiceal neoplasm but cannot definitely distinguish between appendicitis and neoplastic lesions

- Definitive diagnosis is by surgical resection and pathologic examination

- Differential diagnosis for appendiceal neoplasms includes appendicitis, mesenteric or duplication cysts, Meckel diverticulum, simple mucoceles, and other types of neoplasms

- Approach to treatment is dependent on the presence of metastatic disease (either peritoneal or distant) and whether the patient is symptomatic

- Management of nonmetastatic disease usually involves surgical resection; extent of resection is dependent on histologic findings

- LAMN or HAMN: simple appendectomy is likely sufficient

- Appendiceal adenocarcinoma: formal right hemicolectomy is recommended

- Appendiceal NENs: dependent on the size and grade of the lesion

- Adjuvant chemotherapy should be considered for stage II or III appendiceal adenocarcinoma

- Patients with PMP or peritoneal metastasis should be referred to a center specializing in peritoneal malignancies

- Patients with distant metastasis should be referred to a medical oncologist for systemic therapy

- Surveillance after resection is dependent on histology

- LAMN or HAMN likely needs surveillance with cross-sectional imaging (ie, MRI of the abdomen) every 6 to 12 months for 2 years

- Appendiceal adenocarcinoma should be monitored similarly to colon cancer

- Appendiceal NEN surveillance is dependent on the size and grade of the lesion

- Prognosis of appendiceal neoplasms ranges widely

- Completely resected LAMNs have excellent prognosis overall

- Prognosis of appendiceal adenocarcinomas is dependent on stage and differentiation

- Prognosis of appendiceal NENs is dependent on tumor size and presence of metastasis

Alarm Signs and Symptoms

- In patients with cross-sectional imaging performed for appendicitis, but with imaging characteristics consistent with mucin, wall calcifications, wall irregularity, and soft tissue thickening without associated wall thickening or fat stranding, an appendiceal neoplasm should be suspected

- PMP should be suspected in patients with vague symptoms such as fatigue, weight gain, chronic abdominal pain, and early satiety

- Rarely, patients may present with “carcinoid syndrome” (eg, facial flushing, diarrhea, dyspnea); this should raise suspicion for metastatic NEN

- Appendiceal neoplasms may be discovered intraoperatively. In this case, perform a limited resection (eg, appendectomy alone) if the appendix appears grossly abnormal

Introduction

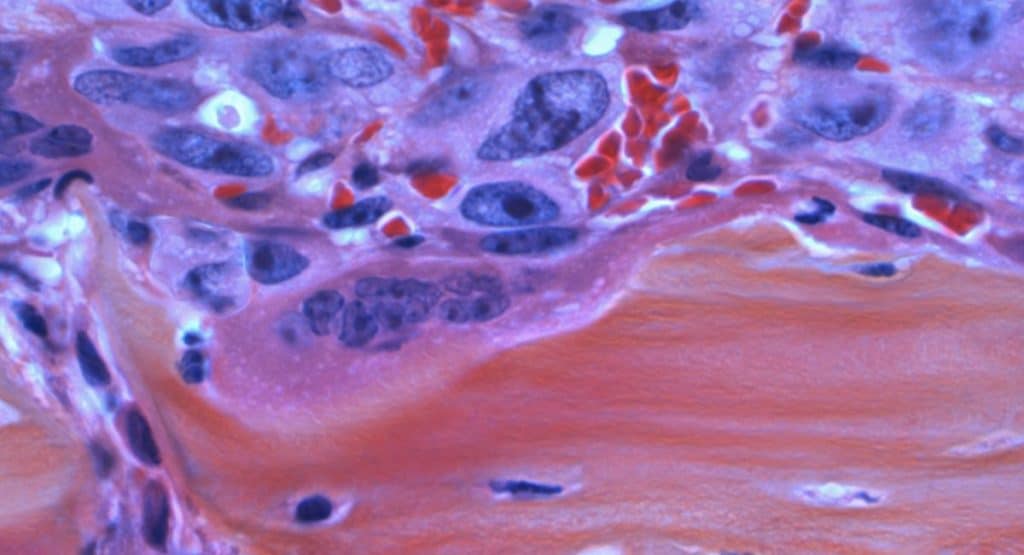

Figure 1. Histologic classification of appendiceal neoplasms.Dotted lines indicate that GCAs and MiNENs exhibit both neuroendocrine and epithelial features; the behavior of GCAs is closer to that of epithelial adenocarcinomas, whereas MiNENs are treated like NECs. GCA, goblet cell adenocarcinoma; HAMN, high-grade appendiceal neoplasm; LAMN, low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm; MiNEN, mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasm; NEC, neuroendocrine carcinoma; NET, neuroendocrine tumor.

Figure 1. Histologic classification of appendiceal neoplasms.Dotted lines indicate that GCAs and MiNENs exhibit both neuroendocrine and epithelial features; the behavior of GCAs is closer to that of epithelial adenocarcinomas, whereas MiNENs are treated like NECs. GCA, goblet cell adenocarcinoma; HAMN, high-grade appendiceal neoplasm; LAMN, low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm; MiNEN, mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasm; NEC, neuroendocrine carcinoma; NET, neuroendocrine tumor.

- Appendiceal neoplasms are benign and malignant neoplasms that arise from epithelial or neuroendocrine cells within the appendix

- Appendiceal neoplasms are histologically classified into epithelial neoplasms and NENs (neuroendocrine neoplasms) (Figure 1)

- Epithelial neoplasms can be subdivided into invasive and noninvasive neoplasms

- Invasive neoplasms include invasive adenocarcinoma and goblet cell adenocarcinomas

- Goblet cell adenocarcinomas exhibit both neuroendocrine and epithelial features; however, they often exhibit much more aggressive behavior, making them more similar to epithelial adenocarcinoma1

- Noninvasive neoplasms include LAMNs (low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms) and HAMNs (high-grade appendiceal neoplasms)

- Polyps of the appendix are rare noninvasive neoplastic lesions. These resemble the polyps found in the colon

- Epithelial neoplasms can also be classified based on mucin production (eg, mucinous versus nonmucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma)

- Mucinous appendiceal lesions are also clinically classified as appendiceal mucoceles

- Appendiceal mucoceles can occur without neoplastic changes to the epithelial cells; in this setting, they are also known as retention cysts

- Invasive neoplasms include invasive adenocarcinoma and goblet cell adenocarcinomas

- NENs include well-differentiated NETs (neuroendocrine tumors), poorly differentiated NECs (neuroendocrine carcinomas), and MiNENs (mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasms)12

- MiNENs are a combination of NECs and adenocarcinomas. They are treated like NECs

- Epithelial neoplasms can be subdivided into invasive and noninvasive neoplasms

- Rarer appendiceal neoplasms, including melanoma, leiomyoma, lipoma, fibroma, neuroma, lymphangioma, and metastatic lesions, are not discussed in this Clinical Overview

- PMP (pseudomyxoma peritonei) refers to diffuse spread of mucin throughout the peritoneum

- PMP is not a histopathologic diagnosis (as the term is often colloquially used) but rather a clinical syndrome often associated with a mucinous appendiceal lesion

- PMP is often associated with ruptured LAMN or mucinous adenocarcinoma of the appendix

Background Information

- Appendiceal neoplasms are rare entities. Therefore, much of the evidence is based on retrospective analyses that span many years

- Analysis may be limited due to changes in the histologic classification of certain pathologies, most notably PMP

- Recommendations are often extrapolated from experience with related, more common pathologies, such as colorectal adenocarcinoma

Epidemiology

- Most recent estimate for the incidence of appendiceal tumors is approximately 0.97 per 100,000 people34

- Epithelial neoplasms likely account for the most, with an estimated incidence of 0.70 per 100,000 people3

- Incidence of LAMNs or HAMNs is poorly characterized, because previous studies often did not distinguish LAMNs or HAMNs from adenocarcinomas

- Incidence of appendiceal NENs is estimated to be approximately 0.16 per 100,000 people5

- Most appendiceal neoplasms are discovered incidentally in the surgical specimen after appendectomy

- It is estimated that epithelial tumors and NENs can be found in approximately 1% of all appendectomy specimens6789

- Appendiceal neoplasms appear to have a slight female predominance46

- Epithelial neoplasms are most often detected in patients in their 50s to 60s,10 whereas NENs are most often diagnosed in patients in their 40s11

Etiology

- Epithelial neoplasms

- Cause of epithelial neoplasms is poorly understood

- It is hypothesized that epithelial neoplasms likely follow an adenoma-carcinoma sequence of carcinogenesis similar to colon cancer

- This sequence typically begins with variants in APC, followed by variants in KRAS and TP53 (among other genes)12

- NENs

- NETs and carcinomas arise from neuroendocrine cells, which are differentiated cells that secrete a variety of peptides and hormones based on their organ of origin13

- Currently, there is no clear genetic pathway to explain tumorgenesis from differentiated neuroendocrine cells1

What are the Risk Factors and Associations?

- Epithelial neoplasms

- Risk factors likely mirror those of colorectal cancer

- Major risk factors include:1415

- Hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes (including familial adenomatous polyposis, hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, MUTYH-associated polyposis)

- Personal or family history of colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Older age

- Black race or ethnicity

- Obesity

- Diabetes

- Smoking

- High red or processed meat intake

- Excessive alcohol intake

- NENs16

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and neurofibromatosis type 1 confer the highest risk

- Other risk factors include:

- Age older than 65 years

- Female sex

- White race or ethnicity

- History of excessive alcohol intake

- Smoking

- Obesity

- Family history of gastrointestinal malignancy

- Inflammatory bowel disease

How is Appendiceal Neoplasms Diagnosed?

Approach to Diagnosis

- Most appendiceal neoplasms are discovered at the time of appendectomy or incidentally in the surgical specimen postoperatively

- Most appendiceal neoplasms are asymptomatic, though appendiceal adenocarcinomas are more likely to present with appendicitis17

- Patients with PMP often present with progressive abdominal girth and may undergo cross-sectional imaging for this reason

- Preoperative suspicion for appendiceal neoplasms most often occurs in the setting of cross-sectional imaging performed when evaluating patients for suspected appendicitis

- Imaging findings suspicious for appendiceal neoplasms include wall calcification, wall irregularity, and soft tissue thickening without associated wall thickening or fat stranding

- Alternatively, appendiceal neoplasms may also be discovered incidentally. Most often, this is in the setting of cross-sectional imaging performed for other reasons

- A thorough history and physical examination are key in the evaluation of patients with suspected (or confirmed) appendiceal neoplasms

- Definitive diagnosis of appendiceal neoplasms is by surgical resection. In almost all circumstances, do not biopsy (percutaneously or surgically) an appendiceal neoplasm18

- If a grossly abnormal appendix is encountered during an unrelated surgical procedure, an appendectomy should be performed.19 There is no need to perform a prophylactic right hemicolectomy in this scenario

- Primary appendiceal NENs typically do not present with “carcinoid” syndrome (eg, flushing, diarrhea, bronchospasm) unless there is extensive metastasis

- If these symptoms are present, then perform a workup for potential metastatic disease, including a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis, and/or DOTATATE PET-CT20

- Appendiceal neoplasms are generally staged pathologically after evaluation of the surgical specimen

- For neoplasms not discovered incidentally, clinical staging is achieved by cross-sectional imaging, as described in the Imaging Studies section below

Diagnostic Criteria

- A definitive diagnosis of appendiceal neoplasms is established by pathologic review of the surgical specimen

Staging or Classification

Staging

- Appendiceal neoplasms are staged per American Joint Committee on Cancer staging

- Epithelial neoplasms21

- Tumor

- Tx: cannot assess primary tumor

- T0: no evidence of primary tumor

- Tis: carcinoma in situ (does not invade through the muscularis mucosae)

- Tis(LAMN): LAMN confined to the muscularis propria (acellular mucin or mucinous epithelium may invade into the muscularis propria). T1 and T2 not applicable to LAMN; acellular mucin or mucinous epithelium that extends into the subserosa or serosa should be classified as T3 or T4a, respectively

- T1: tumor invades the submucosa but not into the muscularis propria

- T2: tumor invades the muscularis propria

- T3: tumor invades through the muscularis propria into the subserosa or mesoappendix

- T4: tumor invades the visceral peritoneum (acellular mucin or mucinous epithelium may involve the serosa of the appendix or mesoappendix, or adjacent organs or structures)

- T4a: tumor invades through the visceral peritoneum (acellular mucin or mucinous epithelium involving the serosa of the appendix or mesoappendix)

- T4b: tumor directly invades or adheres to adjacent organs or structures

- Node

- Nx: cannot assess regional LNs (lymph nodes)

- N0: no regional LN metastasis

- N1: 1 to 3 regional LNs positive (ie, tumor in LN 0.2 mm or greater) or any number of tumor deposits present and all identifiable LNs negative

- N1a: 1 regional LN positive

- N1b: 2 or 3 regional LNs positive

- N1c: no regional LN positive, but tumor deposits present in the subserosa or mesentery

- N2: 4 or more regional LNs positive

- Metastasis

- cM0: no distant metastasis

- cM1: distant metastasis

- cM1c: metastasis to sites other than the peritoneum

- pM1: microscopic confirmation of distant metastasis

- pM1a: intraperitoneal acellular mucin; no identifiable tumor cells in disseminated peritoneal mucinous deposits

- pM1b: intraperitoneal metastasis only

- pM1c: microscopic confirmation of metastasis to sites other than the peritoneum

- Grade

- Gx: grade cannot be assessed

- G1: well differentiated

- G2: moderately differentiated

- G3: poorly differentiated

- Staging

- Stage 0: Tis or Tis(LAMN), N0, M0, and any grade

- Stage I: T1 or T2, N0, M0, and any grade

- Stage IIA: T3, N0, M0, and any grade

- Stage IIB: T4a, N0, M0, and any grade

- Stage IIC: T4b, N0, M0, and any grade

- Stage IIIA: T1 or T2, N1, M0, and any grade

- Stage IIIB: T3 or T4, N1, M0, and any grade

- Stage IIIC: any T, N2, M0, and any grade

- Stage IVA: any T, any N, and M1a with any grade or M1b with G1

- Stage IVB: any T, any N, and M1b with G2, G3, or Gx

- Stage IVC: any T, any N, M1c, and any grade

- Tumor

- NENs22

- Tumor

- Tx: cannot assess primary tumor

- T0: no evidence of primary tumor

- T1: tumor 2 cm or less in greatest dimension

- T2: tumor greater than 2 cm but 4 cm or less in greatest dimension

- T3: tumor greater than 4 cm in greatest dimension or with subserosal invasion or involvement of the mesoappendix

- T4: tumor perforates the peritoneum or directly invades other adjacent organs or structures (excluding direct mural extension to the adjacent subserosa)

- Node

- Nx: cannot assess regional LNs

- N0: no regional LN metastasis

- N1: regional LN metastasis

- Metastasis

- M0: no distant metastasis

- M1: distant metastasis

- M1a: metastasis confined to the liver

- M1b: metastasis in at least 1 extrahepatic site

- M1c: hepatic and extrahepatic metastases

- Staging

- Stage I: T1, N0, and M0

- Stage II: T2 or T3, N0, and M0

- Stage III: T4 with N0 or any T with N1, M0

- Stage IV: any T, any N, and M1

- Tumor

Classification

- Histologic classification of appendiceal neoplasm subtypes is discussed in the Terminology section and illustrated in Figure 1

- PMP is classified histologically per categories developed by Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International19232425

- Acellular mucin

- PMP most often occurs from a ruptured LAMN, resulting in peritoneal spread of mucin without epithelial cells

- PMP with low-grade histologic features

- Abundant extracellular mucin containing scant epithelial cells with little cytologic atypia or mitotic activity

- Also known as disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis or low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei

- PMP with high-grade histologic features

- More abundant epithelial cells with cytologic atypia, as seen in carcinoma

- Also known as peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis or high-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei

- PMP with signet ring cells

- Any lesion with signet ring cell component

- Also known as high-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei with signet ring cells

- Acellular mucin

- WHO classification and grading are used for NENs (Table 1)

- Used to establish a common nomenclature to describe the clinical behavior of NENs

- Well-differentiated NETs have increasingly aggressive behavior with increasing mitotic rate and Ki-67 index, though they remain less aggressive overall compared with NECs

- MiNENs show a combination of NECs and adenocarcinoma features and behave more closely to NECs2

Table 1. WHO’s 2019 classification and grading for NENs.

| Terminology | Differentiation | Grade | Mitotic rate (mitoses/2 mm2) | Ki-67 index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NET, G1 | Well differentiated | Low | Less than 2 | Less than 3% |

| NET, G2 | Intermediate | 2-20 | 3%-20% | |

| NET, G3 | High | More than 20 | More than 20% | |

| NEC, small-cell type | Poorly differentiated | High | More than 20 | More than 20% |

| NEC, large-cell type | More than 20 | More than 20% | ||

| MiNEN | Well or poorly differentiated | Variable | Variable | Variable |

Caption: MiNEN, mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasm; NEC, neuroendocrine carcinoma; NEN, neuroendocrine neoplasms; NET, neuroendocrine tumor.

From Nagtegaal ID et al. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76(2):182-188, Table 2.

Workup

History

- Perform a thorough history, specifically current symptoms and previous surgical and medical history

- Many tumors will be completely asymptomatic and can only be found incidentally on imaging or at surgery

- Because appendicitis may be a concomitant finding, patients may present with symptoms such as abdominal pain, fevers, chills, nausea, and vomiting

- Vague symptoms such as fatigue, weight gain, chronic abdominal pain, and early satiety may indicate PMP

- Advanced tumors may cause mass effects with resultant symptoms of bowel or ureteral obstruction

- Occasionally, patients may also report colicky abdominal pain with gastrointestinal bleeding. This is likely due to intermittent intussusception of the mucinous lesion

- Patients with suspected NENs should be asked regarding symptoms of “carcinoid syndrome,” including facial flushing, diarrhea, and dyspnea; presence of such symptoms suggests metastatic disease

- If an appendectomy has already been performed, a review of the previous operative note and pathology report is imperative

Physical Examination

- Perform a thorough physical examination, concentrating on the abdominal and pelvic examinations

- Rule out peritonitis, though this is rare even in the setting of acute appendicitis

- Examine for abdominal scars that may indicate a previous surgery

- PMP most often presents with nonspecific increased abdominal girth

- Rarely, PMP may present as ventral, incisional, or inguinal hernias2627

Laboratory Tests

- Tumor markers are checked to establish baseline measures for future surveillance and disease monitoring. This is not done to establish a diagnosis

- For patients with epithelial neoplasms, collect a baseline carcinoembryonic antigen level28

- Utility of CA 19-9 (carbohydrate antigen 19-9) and CA 125 (cancer antigen 125) is less clear, but they may be of some benefit in patients with PMP1929

- For patients with appendiceal NENs, collect a baseline serum chromogranin A level. A 24-hour urine collection for 5-HIAA (5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid) is also reasonable.19 However, the utility of these tests is debated

- For patients undergoing surgery, collect a CBC, basic metabolic panel, INR, and type and screen

Imaging Studies

- Appendiceal neoplasms are most often detected incidentally when cross-sectional imaging is performed during the workup of appendicitis30

- Most often, a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast is performed

- Can often suggest an appendiceal neoplasm but cannot definitively distinguish between appendicitis (or other non-neoplastic lesions) and neoplastic lesions

- Wall calcifications, wall irregularities, soft tissue thickening without associated wall thickening or fat stranding, presence of mucin, and adjacent lymphadenopathy may suggest a neoplastic lesion1331

- Patients may present with both appendicitis and a neoplastic lesion

- An abdominal ultrasonography can also suggest an appendiceal neoplasm

- Obtain a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast if ultrasonography suggests an appendiceal neoplasm

- Most often, a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast is performed

- Staging scans

- Obtain a CT scan or MRI of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis in all patients with suspected or confirmed appendiceal adenocarcinoma2829

- NETs 2 cm or less do not require staging scans. For NETs greater than 2 cm, positive margins or nodes from initial resection, or incompletely resected, a multiphasic CT or MRI of the abdomen and pelvis should be performed20

- In patients with NECs, a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis should be performed with consideration for PET-CT and brain MRI20

- NEN-specific imaging

- It is not necessary to obtain NEN-specific imaging (eg, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy) for all patients with appendiceal NENs20

- In patients with suspected metastatic appendiceal NENs (eg, those with “carcinoid syndrome”), obtain a DOTATATE PET-CT.20 Alternatively, a combination of CT or MRI plus somatostatin receptor scintigraphy is reasonable19

Diagnostic Procedures

- Obtain a colonoscopy in all patients diagnosed with, or suspected to have, an appendiceal neoplasm due to the increased risk of harboring a synchronous colonic lesion1929

- If the diagnosis is established preoperatively (rare), then perform the colonoscopy before planned surgical resection

- Otherwise, perform the colonoscopy after the patient has recovered from surgery (usually 4-6 weeks postoperatively)

- In most cases, do not biopsy a suspected appendiceal neoplasms given the potential risk of peritoneal seeding18

- Appendiceal neoplasms are most commonly discovered at the time of appendectomy or incidentally in the surgical specimen postoperatively

- Most common indication for appendectomy is for the treatment of presumed appendicitis

- Considering the increased utilization of nonoperative management in appendicitis, the decision for interval appendectomy in these cases is complex

- Older adults, those with indeterminant imaging, and those with periappendiceal abscess seem to be at higher risk for appendiceal cancer.32333435 Unless there are prohibitive perioperative risk factors, these patients should undergo interval appendectomy

- If there are imaging findings concerning for appendiceal neoplasm, appendicitis should not be managed nonoperatively

- Patients without appendicitis but with an incidentally discovered suspected appendiceal neoplasm should be treated with an appendectomy to obtain a pathologic diagnosis19

- Patients diagnosed with PMP should be referred to a center specializing in peritoneal malignancies

Differential Diagnosis of Appendiceal Neoplasms

Table 2. Differential Diagnosis: Appendiceal neoplasms

| Condition | Description | Differentiated by |

|---|---|---|

| Appendicitis | Inflammation or infection of the appendix | Periappendiceal inflammation or abscess on cross-sectional imaging |

| Mesenteric or duplication cyst | Rare congenital anomalyEpithelial-lined cyst that arises from the mesentery or gastrointestinal tract | Anatomic evaluation on cross-sectional imagingResection offers definitive diagnosis |

| Meckel diverticulum | Congenital anomaly resulting in a true diverticulum of the small intestine | Anatomic evaluation on cross-sectional imagingMay need endoscopy, Meckel scan, or surgical exploration for definitive diagnosis |

| Appendiceal non-neoplastic mucoceles | Non-neoplastic process leading to chronic luminal distention due to continued mucin production by mucosal epithelium | Resection offers definitive pathologic diagnosis and differentiation from neoplastic mucinous lesions |

| Colonic (cecal) or terminal ileum lesion | Cecal or terminal ileal neoplasms may mimic appendiceal neoplasms due to proximity | High-quality cross-sectional imaging may be helpful, though a colonoscopy with intubation of the terminal ileum will provide greater detail |

| Retroperitoneal mass | Retroperitoneal masses (eg, lymphoma, sarcoma) in the right lower quadrant may mimic due to proximity | Colonoscopy will differentiate luminal lesion from retroperitoneal lesionHigh-quality cross-sectional imaging also helpful |

| Adnexal or ovarian lesion | Symptoms may mimic appendicitis in females; cause ranges from benign (eg, ovarian cyst) to malignant (mucinous cystadenoma) | Cross-sectional imaging and ultrasonographic evaluation are necessaryMay require resection for histopathologic diagnosis |

How is Appendiceal Neoplasms treated?

Approach to Treatment

- Goal of treatment is to prolong survival in patients with appendiceal neoplasms, though this needs to be individualized based on specific tumor pathology, patient characteristics, and overall goals of care with consideration for quality of life

- Treatment approach is determined by the presence of metastatic disease and symptoms at the time of diagnosis

- Management of appendiceal neoplasms is largely based on expert opinion and extrapolated from experience with other neoplasms, such as colon adenocarcinoma and other gastrointestinal endocrine neoplasms

- Nonmetastatic disease192028

- For patients with suspected epithelial tumors or NENs, perform upfront surgical resection

- Extent of the surgical resection (appendectomy alone versus right hemicolectomy) is dependent on factors described below (see the Treatment Procedures section)

- Adjuvant chemotherapy should be considered for stage II or III appendiceal adenocarcinoma28

- Use of adjuvant chemotherapy for NENs and LAMNs or HAMNs is not indicated20

- Peritoneal metastasis192028

- Preoperatively suspected and asymptomatic patients

- Refer these patients to a center specializing in peritoneal malignancies to evaluate for possible CRS (cytoreductive surgery) with or without HIPEC (hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy)19

- Preoperatively suspected and symptomatic patients

- Symptoms are most likely due to appendicitis, which can lead to sepsis and/or perforation if left untreated3036

- If clinically stable, attempt a course of nonoperative management with IV antibiotics (eg, piperacillin-tazobactam)

- If there is an abscess of size greater than 3 cm and imaging characteristics not consistent with mucin, consult an interventional radiologist to evaluate for percutaneous drainage37

- Percutaneous drainage should not be attempted if there is concern for mucin, given the theoretical risk of intraperitoneal seeding

- In the rare scenario of clinical instability where the patient has not responded to nonoperative measures, perform a limited resection (most often appendectomy alone), peritoneal washings with cytology, and biopsy of suspicious peritoneal lesions

- Refer this patient to a center specializing in peritoneal malignancies

- In cases of obstruction, either due to peritoneal implants or more rarely, the appendiceal lesion, then attempt a course of nonoperative management barring any emergent surgical indications (eg, closed-loop obstruction)

- Symptoms are most likely due to appendicitis, which can lead to sepsis and/or perforation if left untreated3036

- Intraoperatively encountered peritoneal metastatic disease

- In this scenario, perform an appendectomy (if technically possible), peritoneal washings with cytology, and biopsy of suspicious peritoneal lesions

- Unless there are extraordinary circumstances, do not perform cytoreduction at the index operation

- Refer this patient to a center specializing in peritoneal malignancies to evaluate for possible CRS or HIPEC

- Preoperatively suspected and asymptomatic patients

- Distant metastasis192028

- This is more likely in patients with appendiceal adenocarcinoma or NECs

- Most common sites of distant metastasis are the liver and/or lung38

- In patients with symptomatic appendicitis, attempt a course of nonoperative management with IV antibiotics (eg, piperacillin-tazobactam)36 to minimize perioperative risks and any possible delay in cytotoxic chemotherapy

- In the rare clinical scenario of sepsis or obstruction, perform a limited resection (ideally appendectomy alone) if technically possible36

- Referral to a medical oncologist for systemic therapy

- Treatment of metastatic appendiceal adenocarcinoma closely follows the pathway for metastatic colon cancer28

- Treatment of metastatic NENs may include the use of octreotide, everolimus, PRRT (peptide receptor radionuclide therapy), and cytotoxic chemotherapy20

- Decision for metastasectomy is highly nuanced and requires discussion among multiple specialties, ideally in the setting of a multidisciplinary tumor board

Drug Therapy

- There are currently no medications approved specifically for the treatment of appendiceal neoplasms

- Systemic therapies, including cytotoxic chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and PRRT options, exist for the treatment of appendiceal neoplasms in the adjuvant or metastatic setting

- LAMNs or HAMNs

- Completely resected LAMNs or HAMNs do not need any adjuvant therapy

- Appendiceal adenocarcinoma28

- Adjuvant therapy is extrapolated from experience with colon cancer and typically consists of cytotoxic chemotherapy, most commonly FOLFOX (leucovorin-fluorouracil-oxaliplatin) or CAPEOX (capecitabine-oxaliplatin) for 3 to 6 months

- Patients with stage I cancer do not need any adjuvant therapy

- Patients with stage III (node-positive) cancer typically receive 3 to 6 months of adjuvant chemotherapy

- Patients with high-risk stage II cancer should also be considered for adjuvant chemotherapy

- High-risk features include T4, poor differentiation, bowel or tumor perforation, and lymphovascular or neurovascular invasion

- Patients with stage IV metastatic disease are treated similarly to those with metastatic colon cancer, which most often consists of cytotoxic chemotherapy regimens (FOLFOX, CAPEOX, FOLFIRI [leucovorin-fluorouracil-irinotecan]) with or without bevacizumab (or other immunotherapy based on molecular targets)

- Typically, there is no role for adjuvant radiation therapy

- Use of neoadjuvant therapy (radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy) for locally advanced lesions should be done in the setting of a multidisciplinary tumor board discussion

- Appendiceal NENs20

- In general, completely resected appendiceal NETs do not need further adjuvant treatment, especially if they are smaller than 2 cm

- Role of adjuvant therapy in NENs larger than 2 cm is not well established

- Factors that harbor increased risk for recurrence and/or metastatic disease include size greater than 2 cm and poor differentiation (most often based on Ki-67 index and mitotic rate)

- Locally advanced, recurrent, or metastatic NETs that are unresectable should be considered for octreotide therapy, with consideration for more advanced therapy (eg, everolimus, PRRT, cytotoxic chemotherapy) with disease progression

- Cytotoxic chemotherapy options include fluorouracil, capecitabine, dacarbazine, oxaliplatin, and temozolomide

- Liver-directed therapy and radiation therapy are other options for locoregional disease

- Patients with poorly differentiated NECs should be considered for a combination of resection (if possible), cytotoxic chemotherapy, and radiation therapy

- If disease progresses, can consider more advanced therapy options (eg, everolimus, PRRT, immunotherapy)

- Cytotoxic chemotherapy options include carboplatin-cisplatin + etoposide-irinotecan, FOLFIRI, FOLFOX, and temozolomide ± capecitabine

- Given the rarity of these lesions, consultation with a specialized center is indicated

- In general, completely resected appendiceal NETs do not need further adjuvant treatment, especially if they are smaller than 2 cm

- LAMNs or HAMNs

Table 3. Drug Therapy: Appendiceal neoplasms.

| Medication | Drug class | Common regimens | Life-threatening or dose-limiting adverse reactions | Notable or nonemergent adverse reactions | Special considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CarboplatinD1 | Alkylating agent—platinum | Carboplatin + etoposide | AnaphylaxisBone marrow suppressionNausea/vomitingNephrotoxicity | Electrolyte lossOtotoxicityPeripheral neuropathySecondary malignancy | Avoid coadministering nephrotoxic or ototoxic agentsEnsure adequate hydration |

| CisplatinD2 | Alkylating agent—platinum | Cisplatin + etoposide | AnaphylaxisBone marrow suppressionNausea/vomitingNephrotoxicityOcular toxicity | Electrolyte lossOtotoxicityPeripheral neuropathySecondary malignancy | Avoid coadministering nephrotoxic or ototoxic agentsEnsure adequate hydrationCisplatin has been associated with optic neuritis, papilledema, vision lossEffective contraception required during and after therapy for 14 months for females of reproductive potential and for 11 months for males with female partners of reproductive potential |

| OxaliplatinD3 | Alkylating agent—platinum | Capecitabine + oxaliplatin ± bevacizumabFluorouracil + oxaliplatin + leucovorin ± bevacizumab | AnaphylaxisBleedingBone marrow suppressionNausea/vomitingPeripheral sensory neuropathyPRESPulmonary fibrosisQT prolongation and ventricular arrhythmiasRhabdomyolysis | DiarrheaFatigueIncreased hepatic enzymesStomatitis | Effective contraception required during and after therapy for 9 months for females of reproductive potential and for 6 months for males with female partners of reproductive potential |

| DacarbazineD4 | Alkylating agent—triazene | Dacarbazine monotherapy | AnaphylaxisBone marrow suppressionHepatotoxicity | AnorexiaNausea/vomiting | |

| TemozolomideD5 | Alkylating agent—triazene | Temozolomide monotherapyCapecitabine + temozolomide | Bone marrow suppressionHepatotoxicityPneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia | AlopeciaAnorexiaConstipationFatigueHeadacheNausea/vomitingSecondary malignancySeizures | Effective contraception required during and after therapy for at least 6 months for females of reproductive potential and for at least 3 months for males with female partners of reproductive potential |

| CapecitabineD6 | Antimetabolite—nucleoside metabolic inhibitor | Capecitabine + oxaliplatin ± bevacizumabCapecitabine + temozolomide | Bone marrow suppressionCardiotoxicityDehydrationDermatologic toxicityHyperbilirubinemiaRenal failure | Abdominal painDiarrheaFatigue/weaknessNausea/vomiting | Increased risk of serious or fatal adverse reactions in patients with low or absent dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activityEffective contraception required during and after therapy for 6 months for females of reproductive potential and for 3 months for males with female partners of reproductive potential |

| FluorouracilD7 | Antimetabolite—nucleoside metabolic inhibitor | Fluorouracil monotherapyFluorouracil + oxaliplatin + leucovorin ± bevacizumabFluorouracil + irinotecan + leucovorin ± bevacizumab | Bone marrow suppressionCardiotoxicityDiarrheaHyperammonemic encephalopathyMucositisNeurotoxicityPalmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia (hand-foot syndrome) | Increased risk of serious or fatal adverse reactions in patients with low or absent dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activityEffective contraception required during and after therapy for 3 months for females of reproductive potential and males with female partners of reproductive potential | |

| EverolimusD8 | Kinase inhibitor | Everolimus monotherapy | AnaphylaxisAngioedemaBone marrow suppressionFebrile neutropeniaHypercholesterolemiaHyperglycemiaHyperlipidemiaImpaired wound healingInfectionPneumonitisRadiation sensitization or recallRenal failureStomatitis | Abdominal painAnorexiaAstheniaCoughDiarrheaEdemaFatigueFeverHeadacheNauseaRash | Drug interactions: may need to avoid or adjust dosage of certain drugsAvoid use of live vaccines and close contact with those who have received live vaccines; complete recommended childhood vaccinations before starting treatmentWithhold therapy for at least 1 week before elective surgery and for at least 2 weeks after major surgery and until adequate wound healingTherapeutic drug monitoring may be indicatedEffective contraception required during and after therapy for 8 weeks for females of reproductive potential and for 4 weeks for males with female partners of reproductive potential |

| OctreotideD9 | Somatostatin analog | Octreotide monotherapy | BradycardiaCardiac arrhythmiaCholelithiasisHyperglycemiaHypoglycemiaThyroid dysfunctionVitamin B12 deficiency | Abdominal painBack painDiarrheaDizzinessFatigueFlatulenceHeadacheNausea | Effective contraception required during therapy for females of reproductive potential |

| IrinotecanD10 | Topoisomerase I inhibitor | Fluorouracil + irinotecan + leucovorin ± bevacizumab | AnaphylaxisBone marrow suppressionDiarrheaInterstitial lung diseaseRenal failure | Abdominal painAlopeciaAnorexiaAstheniaConstipationFeverNausea/vomitingWeight loss | Increased risk of neutropenia in patients with reduced UGT1A1 activityEffective contraception required during and after therapy for at least 6 months for females of reproductive potential and for 3 months for males with female partners of reproductive potential |

| EtoposideD11 | Topoisomerase II inhibitor—epipodophyllotoxin | Carboplatin + etoposideCisplatin + etoposide | AnaphylaxisBone marrow suppression | AlopeciaNausea/vomitingSecondary malignancy | Effective contraception required during and after therapy for at least 6 months for females of reproductive potential and for 4 months for males with female partners of reproductive potential |

| BevacizumabD12 | Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor | Fluorouracil + oxaliplatin + leucovorin ± bevacizumabFluorouracil + irinotecan + leucovorin ± bevacizumab | BleedingGastrointestinal perforation or fistulaHeart failureHypertensionImpaired wound healingInfusion-related reactionsNephrotoxicity and proteinuriaOvarian failurePRESThromboembolic events | Abdominal painAnorexiaConstipationCoughDiarrheaDizzinessDyspneaFatigueHeadacheHypomagnesemiaInsomniaMusculoskeletal painNausea/vomitingNephrotoxicityRashUrinary tract infection | Withhold therapy for at least 28 days before elective surgery and for 28 days after major surgery and until adequate wound healingEffective contraception required during and after therapy for 6 months for females of reproductive potential |

Caption: PRES, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome.

Treatment Procedures

- LAMNs or HAMNs

- LAMNs and HAMNs are defined by histologic findings, most often on pathologic review after appendectomy

- Perform an appendectomy with complete resection of the mesoappendix in patients with suspected LAMNs or HAMNs19

- In patients confirmed to have LAMNs or HAMNs on final pathologic evaluation, negative margins, and with no evidence of perforation or peritoneal involvement, do not perform any additional resections29

- If an invasive adenocarcinoma is found on the final surgical specimen, then perform a formal right hemicolectomy19

- Patients with PMP or peritoneal deposits should be referred to a center specializing in peritoneal malignancies to consider for CRS or HIPEC19

- CRS refers to surgical removal of all macroscopic peritoneal disease, which may include removal of the peritoneal lining of the abdomen and any nonessential organs

- HIPEC refers to administration of heated chemotherapy solution directly into the peritoneal cavity

- Appendiceal adenocarcinoma

- Perform a formal right hemicolectomy in patients with appendiceal adenocarcinoma19

- For patients with tumors that are T1, low-grade disease without lymphovascular invasion, and not involving the base of the appendix, appendectomy alone may be acceptable, especially in patients with high perioperative risk factors for colectomy28

- In the setting of peritoneal metastasis, do not routinely perform a right hemicolectomy, because this has not been shown to improve survival19

- Refer these patients to a center specializing in peritoneal malignancies

- Perform a formal right hemicolectomy in patients with appendiceal adenocarcinoma19

- Appendiceal NENs

- Extent of surgical resection is based on size and histology of the lesion19

- Unfortunately, histologic features can only be accurately determined postoperatively. Therefore, return to the operating room for right hemicolectomy is not an uncommon scenario in the setting of unfavorable features on a final pathologic evaluation

- Unfavorable features include mesoappendiceal invasion greater than 3 mm, elevated mitotic index more than 2 mitoses per high-powered field, Ki-67 index more than 3%, and lymphatic or vascular invasion19

- Lesions less than 1 cm without unfavorable features

- Perform an appendectomy with complete mesoappendix resection11929

- Lesions 1 to 2 cm

- Extent of surgical resection is based on a combination of histologic features (if available) and patient comorbidities and preference19

- In most cases, an appendectomy alone is sufficient

- Lesions more than 2 cm

- Perform a formal right hemicolectomy1192939

- Although most lesions are at the tip of the appendix, lesions at the base of the appendix may require extended resection to achieve a negative margin19

- Options include partial cecectomy (with preservation of the ileocecal valve), ileocecectomy, or right hemicolectomy1

- Extent of surgical resection is based on size and histology of the lesion19

Persistent or Recurrent Disease

- LAMNs or HAMNs

- Recurrence of LAMNs or HAMNs most likely presents as recurrent accumulation of intraperitoneal mucin

- Rate of recurrence of HAMNs, given their increased cellular atypia, is assumed to be higher than that of LAMNs40

- Decision for repeat CRS or HIPEC is highly nuanced, and these patients should be evaluated at a specialized center

- Recurrence of LAMNs or HAMNs most likely presents as recurrent accumulation of intraperitoneal mucin

- Appendiceal adenocarcinoma

- Recommendations are extrapolated from colon cancer experience28

- Patients with persistent or recurrent disease who are resectable should undergo a formal right hemicolectomy (if not already performed)

- Patients may also be candidates for cytotoxic chemotherapy (eg, FOLFOX, CAPOX) either before and/or after an attempt at resection

- NENs

- Treatment of recurrent or persistent NENs is highly nuanced and optimal management is not well established. Consultation with a multidisciplinary tumor board is advised20

- In general, if complete resection is possible, then this should be considered (most likely a formal right hemicolectomy if one was not already performed)

- For patients who are unresectable, consider systemic therapy with octreotide

- If persistent progressive disease, then consider everolimus, PRRT, or cytotoxic chemotherapy

- For patients with NECs, consideration of radiation therapy in addition to chemotherapy is appropriate for persistent or recurrent disease

Admission Criteria

- Concurrent appendicitis36

- Patients with appendiceal neoplasms may have concurrent appendicitis

- As described above, patients may require appendectomy or an attempt at nonoperative management with antibiotics; either of these strategies will typically require an admission to the hospital

- For patients with perforated appendicitis, hospital admission for antibiotics and/or percutaneous drainage is typically required

- Postsurgical intervention

- Simple appendectomy

- Typically, these patients can be discharged the same day or next day after a simple appendectomy unless there were intraoperative or postoperative issues of concern

- Right hemicolectomy

- Typically, these patients are admitted to the hospital and use standard ERAS (Enhanced Recovery After Surgery) pathways

- These patients are typically discharged between 2 and 3 days after surgery

- Postoperative complications, including bleeding, wound infection, and enteric or anastomotic leak, and medical complications (eg, thromboembolic disease) require evaluation by practitioners depending on the acuity and may warrant admission

- Simple appendectomy

Special Considerations

Ruptured or Perforated Appendiceal Neoplasms

- Mucinous appendiceal neoplasms

- Evidence-based guidelines are lacking for this scenario; recommendations are based on expert opinion

- When encountered intraoperatively, limit initial resection to appendectomy alone if possible

- Also perform careful inspection of the abdominal cavity and biopsy of any suspicious lesions. Peritoneal cytology can be considered, though its utility is not well established19

- If the perforation involves the right colon and/or mesentery, then a right hemicolectomy may be required

- Do not perform CRS at the index operation19

- Perforation of appendiceal NENs does not seem to affect prognosis and can be managed expectantly41

Follow-Up

Monitoring

- In general, there are no consensus guidelines for surveillance in appendiceal neoplasms

- LAMN or HAMN

- Surveillance guidelines for LAMNs or HAMNs are highly variable

- For completely resected LAMNs, surveillance protocols range from abdominal MRI every 6 to 12 months for 2 years19 to routine postoperative care without additional surveillance42

- Patients with cellular or acellular mucin deposits outside the appendix, or those with perforation, should get CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis every 6 months for 2 years, then annual imaging until 5 years, and then CT scan every 2 years until 10 years after resection19

- This surveillance protocol should also be performed for all HAMNs given the higher risk of recurrence19

- Appendiceal adenocarcinoma

- Although formal surveillance guidelines specifically for appendiceal adenocarcinoma have not been developed, monitoring regimens similar to those used for resected colon cancer are generally followed28

- Stage I

- Colonoscopy 1 year after surgery

- If advanced adenoma is present, repeat in 1 year

- Otherwise, can repeat in 3 years and then every 5 years

- Colonoscopy 1 year after surgery

- Stages II, III, and IV

- History and physical examination every 3 to 6 months for 2 years and then every 6 months for at least 5 years

- Tumor markers every 3 to 6 months for 2 years and then every 6 months for a total of at least 5 years

- Carcinoembryonic antigen is routinely used for colon cancer surveillance; CA 125 and CA 19-9 have also been used for appendiceal adenocarcinoma19

- Cross-sectional imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis every 6 to 12 months for at least 5 years for patients with stage II or III cancer; for patients with stage IV cancer, imaging every 3 to 6 months after surgery for 2 years and then every 6 months for a total of at least 5 years

- CT is the most used imaging modality, but MRI appears superior in detection of peritoneal disease, and is often used for surveillance after CRS or HIPEC19

- PET scan does not appear to change management and is not routinely indicated

- Colonoscopy 3 to 6 months after surgery, if preoperative colonoscopy could not be completed due to obstructing lesion

- Colonoscopy 1 year after surgery otherwise

- If advanced adenoma is present, repeat in 1 year

- Otherwise, repeat in 3 years and then every 5 years

- There is limited evidence supporting prolonged surveillance beyond 10 to 15 years19

- Stage I

- Although formal surveillance guidelines specifically for appendiceal adenocarcinoma have not been developed, monitoring regimens similar to those used for resected colon cancer are generally followed28

- Appendiceal NENs1920

- For tumors 2 cm or less without unfavorable features, there is no need for formal surveillance

- For tumors greater than 2 cm

- Within 12 months postresection: history and physical examination, CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis, and chromogranin A or 5-HIAA; consider CT scan of the chest as indicated

- After 12 months: history and physical examination, CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis, and chromogranin A or 5-HIAA every 12 to 24 months for up to 10 years postresection. Consider CT scan of the chest as indicated

- Patients with tumors 2 cm or less with unfavorable features are surveyed similarly to patients with tumors greater than 2 cm

- Chromogranin A or 5-HIAA levels can correlate with response to therapy or recurrence. However, correlation with imaging is required due to the nonspecific nature of these tumor markers

- If recurrence is suspected on CT imaging, then NEN-specific imaging such as DOTATATE PET-CT is reasonable to confirm findings if there is diagnostic uncertainty

- There is insufficient evidence for the use of NEN-specific imaging during routine surveillance

Complications

- Appendiceal neoplasms may lead to appendicitis and, rarely, peritonitis

- Mucinous appendiceal neoplasms may progress to PMP

- Complications after appendectomy or right hemicolectomy include surgical site infection, anastomotic leak, bleeding, ileus, postoperative bowel obstruction, fistula formation, ureter injury, and risks of anesthesia (including cardiopulmonary complications)

Prognosis

- LAMN or HAMN

- Prognosis is dependent on histology and presence or extent of peritoneal spread

- Non-neoplastic lesions, such as mucoceles or retention cysts and serrated polyps, have excellent overall survival in the range of 91% to 100% after appendectomy104344

- LAMNs confined to the appendix, typically classified as Tis(LAMN), have very rare recurrence

- LAMNs with peritoneal spread also have good 5-year survival, ranging from 79% to 86%45

- Survival rates for HAMNs appear to be similar to those for LAMNs

- However, HAMNs, by definition, exhibit more cellular atypia compared with LAMNs. Therefore, risk of recurrence of HAMNs may be higher, though data are limited40

- Appendiceal adenocarcinoma

- Prognosis is dependent on LN metastasis, distant metastasis, and tumor differentiation1346

- Tumor perforation does not seem to adversely affect prognosis47

- Tumor histology also plays a role, with signet ring cell being the worst, mucinous and intestinal intermediate, and goblet cell the most favorable48

- An analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program registry data from 1973 to 2005 encompassing 931 cases reported overall 5-year survival rates of 81.1% for patients with stage I cancer, 52.6% for patients with stage II cancer, 32.9% for patients with stage III cancer, and 22.7% for patients with stage IV cancer49

- Appendiceal NENs

- Prognosis is dependent on tumor size and presence of metastasis50

- Tumors 2 cm or less have excellent prognosis and rarely metastasize

- However, up to one-third of patients with lesions greater than 2 cm have metastatic disease at diagnosis, most commonly to the liver515253

- Perforation does not appear to negatively affect prognosis and therefore, should not affect treatment or surveillance41

- A retrospective review of 114 patients who presented to a tertiary referral center from 1998 to 2019 reported 5- and 10-year survival stratified by stage group as shown in Table 4

Table 4. 5- and 10-year overall survival for patients with appendiceal NETs stratified by stage group.

| Stage group | 5-year overall survival (%) | 10-year overall survival (%) |

|---|---|---|

| I | 100 | 100 |

| II | 100 | 100 |

| III | 78 | 63 |

| IV | 32 | 17 |

| Overall | 90 | 85 |

Caption: NET, neuroendocrine tumor.

From Landry JP et al. Management of appendiceal neuroendocrine tumors: metastatic potential of small tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(2):751-757.

Referral

- LAMN or HAMN

- In patients with a completely resected LAMN without peritoneal spread, there is no need for additional surveillance other than yearly medical checkup by the patient’s primary care practitioner

- There is limited utility in referring to a specialized center

- In patients with cellular or acellular mucin deposits outside the appendix, or a history of perforation without obvious peritoneal disease, it is reasonable to refer to a center that specializes in peritoneal malignancies

- All patients with a final histology of HAMN should be referred to a specialized center

- In patients with a completely resected LAMN without peritoneal spread, there is no need for additional surveillance other than yearly medical checkup by the patient’s primary care practitioner

- Appendiceal adenocarcinoma

- Depending on the stage, referral to a medical oncologist may be necessary

- In cases of peritoneal disease, referral to a center specializing in peritoneal malignancies is necessary

- Appendiceal NENs

- For patients with NECs or positive LNs, referral to a medical oncologist is recommended

- Patients with tumors greater than 2 cm can also be referred to a medical oncologist, though the utility for adjuvant therapy is unclear

- Referral to a center with experience in appendiceal NENs is reasonable, especially if metastatic disease is present

- For patients with NECs or positive LNs, referral to a medical oncologist is recommended

References

1.Boudreaux JP et al. The NANETS consensus guideline for the diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumors: Well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors of the jejunum, ileum, appendix, and cecum. Pancreas. 2010;39(6):753-766.

View In Article|Cross Reference

2.Nagtegaal ID et al. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76(2):182-188.

View In Article|Cross Reference

3.Marmor S et al. the rise in appendiceal cancer incidence: 2000–2009. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(4):743-750.

View In Article|Cross Reference

4.McCusker ME et al. Primary malignant neoplasms of the appendix: a population-based study from the surveillance, epidemiology and end-results program, 1973-1998. Cancer. 2002;94(12):3307-3312.

View In Article|Cross Reference

5.Yao JC et al. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(18):3063-3072.

View In Article|Cross Reference

6.Smeenk RM et al. Appendiceal neoplasms and pseudomyxoma peritonei: a population based study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34(2):196-201.

View In Article|Cross Reference

7.Connor SJ et al. Retrospective clinicopathologic analysis of appendiceal tumors from 7,970 appendectomies. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41(1):75-80.

View In Article|Cross Reference

8.Goede AC et al. Carcinoid tumour of the appendix. Br J Surg. 2003;90(11):1317-1322.

View In Article|Cross Reference

9.Bastiaenen VP et al. Routine histopathologic examination of the appendix after appendectomy for presumed appendicitis: is it really necessary? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg (United States). 2020;168(2):305-312.

View In Article|Cross Reference

10.Landen S et al. Appendiceal mucoceles and pseudomyxoma peritonei. Surg Gynecol Obs. 1992;175(5):401-404.

View In Article|Cross Reference

11.Sandor A et al. A retrospective analysis of 1570 appendiceal carcinoids. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;94(3):422-428.

View In Article|Cross Reference

12.Lynch JP et al. The genetic pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2002;16(4):775-810.

View In Article|Cross Reference

13.Tan SA et al. Appendiceal neoplasms. In: Steele SR et al, eds. The ASCRS Textbook of Colon and Rectal Surgery. 4th ed. Springer Nature; 2022:577-586.

14.Chan AT et al. Primary prevention of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(6):2029-2043.e10.

View In Article|Cross Reference

15.Siegel RL et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(3):233-254.

View In Article|Cross Reference

16.Alkhayyat M et al. Epidemiology of neuroendocrine tumors of the appendix in the USA: a population-based national study (2014-2019). Ann Gastroenterol. 2021;34(5):713-720.

View In Article|Cross Reference

17.Ito H et al. Appendiceal adenocarcinoma: long-term outcomes after surgical therapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(4):474-480.

View In Article|Cross Reference

18.Zuzarte JC et al. Fine needle aspiration cytology of appendiceal mucinous cystadenoma: a case report. Acta Cytol. 1996;40(2):327-330.

View In Article|Cross Reference

19.Glasgow SC et al. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, clinical practice guidelines for the management of appendiceal neoplasms. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62(12):1425-1438.

View In Article|Cross Reference

20.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors. Version 1.2023. Accessed March 1, 2024.

View In Article|Cross Reference

21.Overman MJ et al. Appendix. AJCC Cancer Staging System. Version 9. American Joint Committee on Cancer, American College of Surgeons; 2022.

22.Overman MJ et al. Appendix–carcinoma. In: Amin MB et al; American Joint Committee on Cancer, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017:237-250.

23.Carr NJ et al. The histopathological classification, diagnosis and differential diagnosis of mucinous appendiceal neoplasms, appendiceal adenocarcinomas and pseudomyxoma peritonei. Histopathology. 2017;71(6):847-858.

View In Article|Cross Reference

24.Sugarbaker PH et al. Pseudomyxoma peritonei syndrome. Adv Surg. 1996;30:233-280.

View In Article|Cross Reference

25.Hoehn RS et al. Current management of appendiceal neoplasms. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. March 2021;41:1-15.

View In Article|Cross Reference

26.Shankar S et al. Neoplasms of the appendix: current treatment guidelines. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2012;26(6):1261-1290.

View In Article|Cross Reference

27.Sugarbaker PH. Epithelial appendiceal neoplasms. Cancer J. 2009;15(3):225-235.

View In Article|Cross Reference

28.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): colon cancer. Version 1.2024. Accessed March 1, 2024.

View In Article|Cross Reference

29.Govaerts K et al. Appendiceal tumours and pseudomyxoma peritonei: Literature review with PSOGI/EURACAN clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(1):11-35.

View In Article|Cross Reference

30.Kambadakone A et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria right lower quadrant pain: 2022 update. 2022;19(11):S445-S461.

View In Article|Cross Reference

31.Brassil M et al. Appendiceal tumours–a correlation of CT features and histopathological diagnosis. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2022;66(1):92-101.

View In Article|Cross Reference

32.Lu P et al. Risk of appendiceal cancer in patients undergoing appendectomy for appendicitis in the era of increasing nonoperative management. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120(3):452-459.

View In Article|Cross Reference

33.Loftus TJ et al. Predicting appendiceal tumors among patients with appendicitis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82(4):771-775.

View In Article|Cross Reference

34.Mällinen J et al. Risk of appendiceal neoplasm in periappendicular abscess in patients treated with interval appendectomy vs follow-up with magnetic resonance imaging: 1-year outcomes of the peri-appendicitis acuta randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(3):200-207.

View In Article|Cross Reference

35.Peltrini R et al. Risk of appendiceal neoplasm after interval appendectomy for complicated appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgeon. 2021;19(6):e549-e558.

View In Article|Cross Reference

36.Di Saverio S et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis: 2020 update of the WSES Jerusalem guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15(1):1-42.

View In Article|Cross Reference

37.Expert Panel on Interventional Radiology; Weiss CR et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria radiologic management of infected fluid collections. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(5S):S265:S280.

View In Article|Cross Reference

38.Riihimäki M et al. The epidemiology of metastases in neuroendocrine tumors. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(12):2679-2686.

View In Article|Cross Reference

39.Ricci C et al. Histopathological diagnosis of appendiceal neuroendocrine neoplasms: when to perform a right hemicolectomy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine. 2019;66(3):460-466.

View In Article|Cross Reference

40.Kyang LS et al. Long-term survival outcomes of cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: single-institutional experience with 1225 cases. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120(4):794-802.

View In Article|Cross Reference

41.Madani A et al. Perforation in appendiceal well-differentiated carcinoid and goblet cell tumors: impact on prognosis? A systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(3):959-965.

View In Article|Cross Reference

42.Schuitevoerder D et al. The Chicago consensus on peritoneal surface malignancies: management of appendiceal neoplasms. Cancer. 2020;126(11):2525-2533.

View In Article|Cross Reference

43.Qizilbash AH. Mucoceles of the appendix. Their relationship to hyperplastic polyps, mucinous cystadenomas, and cystadenocarcinomas. Arch Pathol. 1975;99(10):548-555.

View In Article|Cross Reference

44.Soweid AM et al. Diagnosis and management of appendiceal mucoceles. Dig Dis. 1998;16(3):183-186.

View In Article|Cross Reference

45.Misdraji J et al. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: a clinicopathologic analysis of 107 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27(8):1089-1103.

View In Article|Cross Reference

46.Asare EA et al. The impact of stage, grade, and mucinous histology on the efficacy of systemic chemotherapy in adenocarcinomas of the appendix: analysis of the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer. 2016;122(2):213-221.

View In Article|Cross Reference

47.Nash GM et al. Lymph node metastasis predicts disease recurrence in a single-center experience of 70 stages 1–3 appendix cancers: a retrospective review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(11):3613-3617.

View In Article|Cross Reference

48.Turaga KK et al. Importance of histologic subtype in the staging of appendiceal tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(5):1379-1385.

View In Article|Cross Reference

49.Appendix. In: Edge SB et al; AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. Springer; 2010:133-142.

50.Landry JP et al. Management of appendiceal neuroendocrine tumors: metastatic potential of small tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(2):751-757.

View In Article|Cross Reference

51.Moertel CG et al. Carcinoid tumor of the appendix: treatment and prognosis. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(27):1699-1701.

View In Article|Cross Reference

52.Anderson JR et al. Carcinoid tumours of the appendix. Br J Surg. 1985;72(7):545-546.

View In Article|Cross Reference

53.Rostad O. No prognostic indicators for carcinoid neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89(3):151-160.